|

North

Carolina to Give Pills Against Radiation

Potassium

iodide could protect against thyroid cancer in case of radiation exposure Paraphrased

by Steve Waldrop

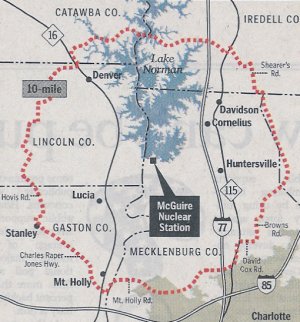

October 25, 2002 Nearly

165,000 people living with 10 miles of the Charlotte area's nuclear plants are

elligible to receive two tiny salt pills later that could help save their lives

in a radiation disaster.

North Carolina counties in the Charlotte area

will distribute free potassium iodide pills from the federal government in October.

Times and places where residents can pick up tablets will be announced later.

Officials in South Carolina say that they haven't decided whether to offer the

pills, which can prevent thyroid cancer caused by radiation. Other N.C. counties

near nuclear plants will make their own plans for distribution.

The pills

don't block all potentially harmful radiation from a nuclear accident. So officials

warn that taking potassium iodide, known as KI, shouldn't make people feel safe.

They still need to evacuate if officials tell them to.

'" This is

a very small silver of protection," said Mecklenburg Health Director Peter

Safir.

People

living more than 10 miles from the plants, aren't eligible for the free pills,

although they might be vulnerable to radiation. Studies suggest that a major nuclear

accident might increase the risk of thyroid cancer more than 100 miles away. People

living more than 10 miles from the plants, aren't eligible for the free pills,

although they might be vulnerable to radiation. Studies suggest that a major nuclear

accident might increase the risk of thyroid cancer more than 100 miles away.

Mecklenburg

County health officials say they've alerted major pharmacy chains that they might

want to increase their local supplies in case they see more demand in the coming

weeks. The Carolinas

have a dozen nuclear plants, including McGuire on Lake Norman and Catawba on Lake

Wylie, both in North Carolina.

Mecklenburg, Gaston, Catawba, Iredell and

Lincoln counties will receive 350,000 pills from the NRC stock. Mecklenburg officials

expect fewer than half the eligible residents to want them. If they run low, however,

local officials may ask for more.

People who work within 10 miles of the

plants will be offered the pill later, officials aren't sure when.

Potassium

iodide is "not very different in its chemical structure from table salt,"

said Dr. Stephen Keener, Mecklenburg County's medical director. Table salt doesn't

protect against radiation.

The pills will come with instructions and should

not be taken unless a disaster occurs. Officials will make an announcement telling

residents when to use them.

Some people are allergic to iodide, and others

can suffer minor side effects, such as rashes. Officials urge people who receive

the pills to check with their doctor if they're not sure it's OK for them.

KI

can be given to people of all ages, although newborns younger than 1 month should

only take an eight of a pill. Infants and children, who have more active thyroid

glands than adults, are at particular risk of thyroid cancer in a radiation-spewing

disaster. KI

can be given to people of all ages, although newborns younger than 1 month should

only take an eight of a pill. Infants and children, who have more active thyroid

glands than adults, are at particular risk of thyroid cancer in a radiation-spewing

disaster.

Potassium iodide received Food and Drug Administration approval

in 1982, three years after the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in Pennsylvania.

For years, health experts urged federal, state and local officials to stockpile

the pills for emergency civilian use. But it took the September 11 terrorist attack

to convince the NRC to act.

Until recently, both Carolinas kept small KI

stockpiles- enough to protect only emergency workers and civilians, who could

not evacuate quickly, such as hospital patients and prison inmates.

Distribution

after a disaster also was a concern, officials would prefer to see residents evacuate

rather than stand in line for pills- which is why they decided to distribute them

to residents now, rather than storing them to pass out after an event.

"Potassium

iodide is not a substitute for evacuation in an emergency," Keener said.

"That is the No. 1, 2 and 3 priority." But

evacuating everyone within 10 miles of the McGuire or Catawba plants could take

at least eight to 24 hours, according to local emergency plans. Less than four

hours is considered optimal by the federal government.

The worst kind of

nuclear accident could release enough radiation within a few hours to pose a potential

cancer risk for people nearby. The chance of that happening, the NRC says, is

very low. |